Review – Arturo Brachetti in “Solo”

the new one man show by and with Arturo Brachetti: Solo

(CENTRAL PALC – 09/02/2018 – ILARIA FARAONI)

After making its debut in Paris the new one man show by and with Arturo Brachetti arrived at Teatro Sistinain Rome (where he will remain until 18 February): his “Solo”.

And there must be a reason if, after so many years, in seeing a show by Brachetti, transformist par excellence, the amazement is intact and the question on everyone’s lips is always the same “But how does he..?”. Standing ovation applauses were numerous, on the evening of the first performance (February 7th).

It is not for nothing that the artist has been included in the Guinness Book of Records as the most prolific and fastest transformer in the world. To his credit Mr. Brachetti also has a Molière award (the French analogue to a Tony Award), a Laurence Olivier Award, and was dubbed Knight of the Arts and Labor by the French Minister of Culture and Commendatore by former Italian President Napolitano.

But there is not only his quick change mastery, in this SOLO: there is the equally astonishing chapeaugraphie, a technique with which Brachetti succeeds in transforming a hat with a hole in the middle – «You have to fill the hole with imagination», his grandfather would have told him – in 25 different headgears and as many characters: it is for him as simple as bending the fabric with a couple of gestures.

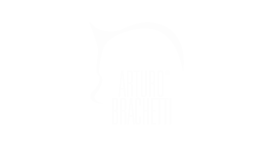

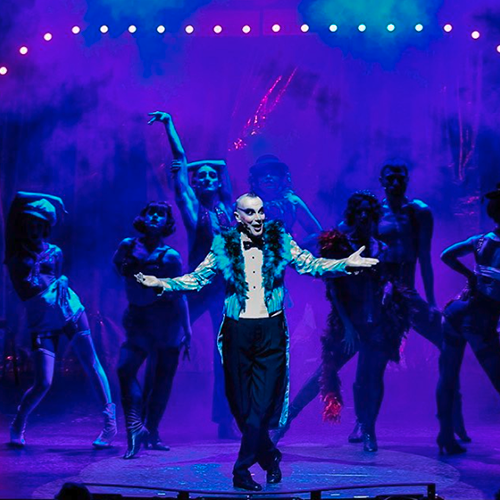

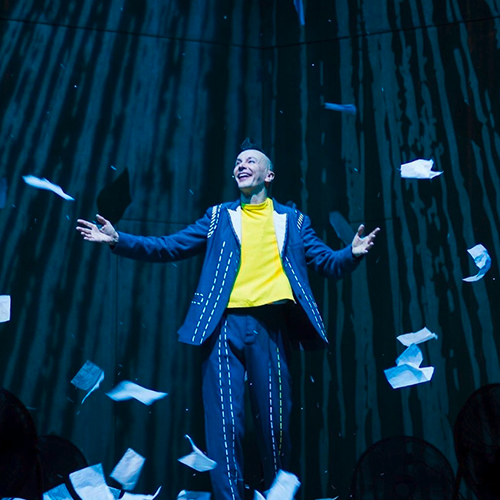

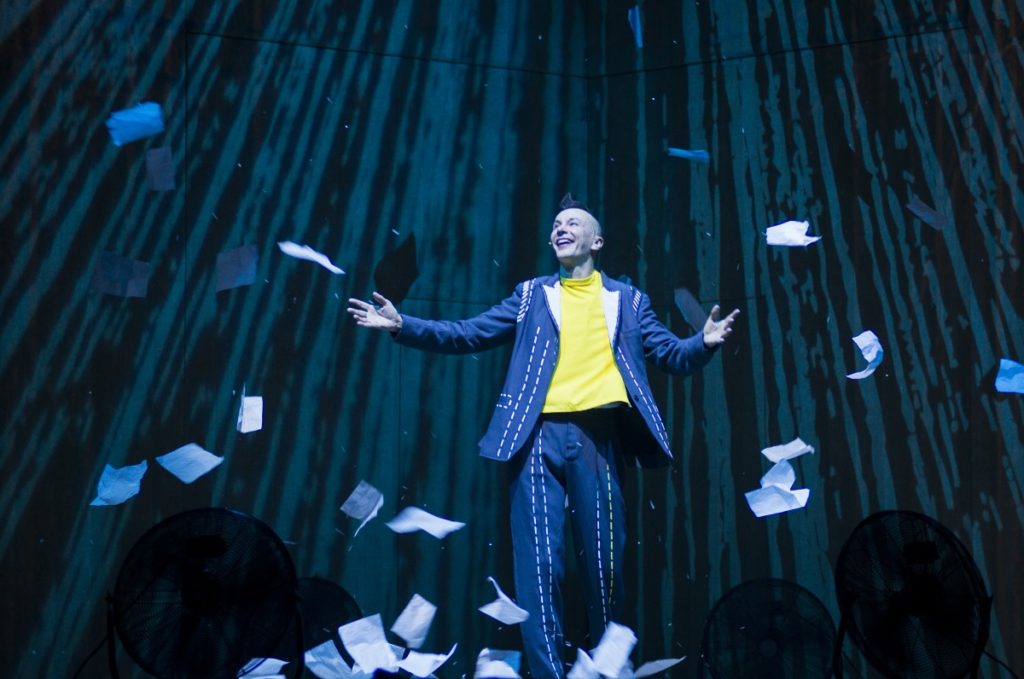

And there’s more: the art of creating real paintings with sand (sand painting), there’s shadow puppetry, there is the use of the latest laser technologies – that the artist had already presented us in the show “Brachetti, what a surprise!” – to create incredible sci-fi atmospheres in the vein of Matrix or Tron. The use of the laser alone, however, would not be enough were it not for the extraordinary skill of Brachetti, Kevin Michael Moore (the mischievous, Peter Pan-esque human shadow accompanying him through the story) and of the entire technical sector, who manage to coordinate perfectly with the human/laser interaction, obtaining very realistic results with a great visual impact, including flight.

Then there is dream and magic (in the broadest sense of the term) that permeate the whole show, transporting the audience in a world suspended by itself, the personal world of Brachetti, which linked the various moments of the show (which would, to be fair, hold up on their own anyway) via the central idea of the miniature house, one “of my memories, of my dreams, of my fears”, as the artist explains to the audience from the stage.

With a mini-camera that projects images directly on screen, one enters the various rooms (seven in total) and through symbolic objects, which will then return at the end of the show, the showman takes us on a journey that evokes the characters of the most popular Disney cartoons and the most famous international singers.

The use of video mapping, which integrates animated images and scenography, allowing Brachetti to enter directly into the pages of a fairytale book or fly very realistically on the Aladdin carpet through the streets of an imaginary Agrabah, is designed to perfection, as are the lights, which allow certain spectacular and poetic effects.

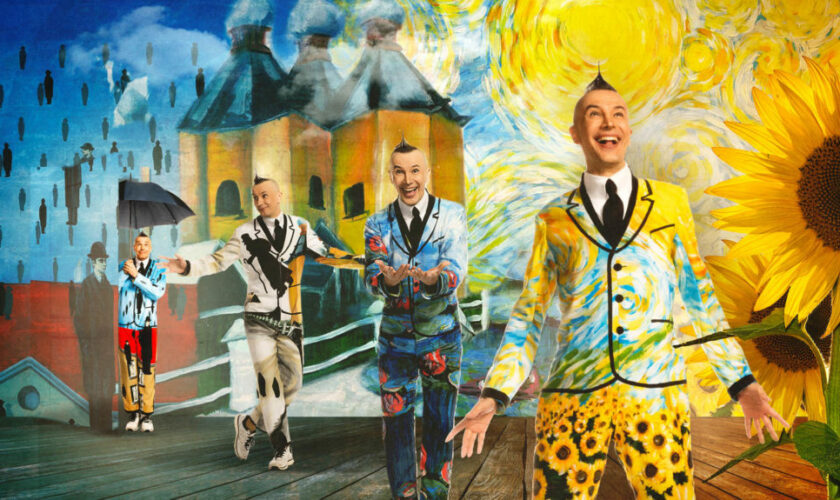

One could still speak of the well-known references such as the paintings by Magritte, Monet or Van Gogh associated with the four seasons or the theme (very dear to the artist) of growth: Brachetti in fact claims he won’t grow old, but will continue to fly, to stoke the fires of imagination: an innermost desire that generates strife, only verbal at first, then physical, between him and his shadow. Or one could recall the poetry that permeates so many of the show’s visual paintings. With all the elements just listed, however, clash a few racier moments as the revisited deeds of Snow White or the tableau that takes place in a kitchen during a wedding. Of these parts the show could very well do without and not lose anything: it could perhaps even gain, since there are already plenty more effective moments of irony and fun.

So it’s better to focus on the tender and melancholic scene of Arturo’s dance with the memory of the flowered gown his mum had sewn, a dress that comes to life by literally flying during the dance.

For the umpteenth time, therefore, there is flight, which in this show is declined in various ways, thus remaining at the center of the whole 90 minutes act. So how could one think of Brachetti without associating him with Peter Pan, another central theme of SOLO? He does not only wear Peter’s clothes, but is also sort of an “Italian dad” to the character, seeing as the eponymous musical directed by Colombi was born in 2006 under the artistic direction of Brachetti, who left his very clear signature, one echoed in certain mesmerizing images of SOLO that stay with the audience.